Wednesday, April 6, 2016

CAPIZ RESPONDERS GOES BUSHCRAFT

I

HAVE NEVER BEEN TO the Province of Capiz. That would be my

destination, however, as I sat inside a Cebu Pacific plane bound for

Iloilo from Cebu on the early morning of July 23, 2015. Coming with

me is Joy Quito, whose organization, the Peace and Conflict

Journalism Network (PECOJON), made possible my appearance there soon

as a resource person for the training of 32 individuals in Basic

Tropical Bushcraft Course.

These

32 individuals belong to the Capiz Archdiocese Disaster Emergency

Responders (CADER), which is a pet project of the director of the

Capiz Archdiocese Social Action Center, Rev. Fr. Mark Q. Granflor. A

private passenger van from the Archdiocese of Capiz whisk me and Joy

from the airport in Cabatuan, then rendezvous with Len Manriquez and

Charlie Saceda of PECOJON, and travel overland to Roxas City over a

scenery of healthy rice fields and friendly people, whose tone of

Hiligaynon are pleasantly sweet to my ears.

Would

I present my lecture in Hiligaynon to these 32 individuals of CADER

or would I prefer to use Cebuano and English? Or in Tagalog,

perhaps? I had been a basic speaker of Hiligaynon as I learned it in

my journeys in the Visayan Sea in 1986-87 but it had eroded through

the years without practice although I could plainly understand what

the Ilonggos would say amongst themselves. Nevertheless, I have to

try. It would be stiff on my part but it is part of the challenge as

a bushcraft instructor.

We

arrive at the place where the Archdiocese of Capiz is founded and the

bronze statue of the late Cardinal Jaime Sin stood prominently as we

proceed to the office of Fr. Mark. After a few minutes, Fr. Mark

invited me and the PECOJON officers – Len, Charlie and Joy – to a

lunch at his grandmother's house in Ivisan, Capiz. Seafoods galore:

steamed mud crabs (Local: alimango), shrimps, mantis shrimps

(hanlilitik) and mussels; blanched seaweeds (lato); and

crabs in thick coconut-milk soup.

The

place where the bushcraft camp would be held is just in the vicinity

yet we have to take the same vehicle in going there. It is now

almost two in the afternoon and the opening of the seminar is a bit

delayed. I found myself inside a local haunt, the Spring Hills

Resort, as the site where I and the participants would spend the next

three days. It is in the village of Malocloc Norte and has two

pools, several cottages and a main hall. It has a small stream

running beside it and verdant vegetation everywhere.

I

found no other place to set up a campsite except at a grassy

volleyball court and a vegetated knoll above it. The participants

are now all accounted for and I introduce myself after opening the

seminar. The heavens begin to growl and I instructed the

participants – to include the PECOJON officers - to set up their

simple shelters under the onslaught of rain, because that would be

the same conditions when you are responding to places hit by

disasters. A few seconds later, it rained hard. All were unprepared

and some were in a state of mild shock at this reality.

As

I have stated to them earlier about this strange sounding activity

called bushcraft, that it is just all about the mind, adaptation and

improvisation; and gears have nothing to do with surviving. The

archdiocese had provided the CADER volunteers several pieces of cheap

3-meter by 3-meter laminated nylon sheets that I have specified for

use in this training. I watched and documented them as they started

to set up their shelters using pieces of rope, foraged wood and

improvised cordage. All sorts of knife lay on the ground everywhere.

I

have done this on purpose to test their levels of individuality and

their teamwork and to make as basis for a critique later on. Each

tarpaulin are assigned to a team of two people and I saw two teams

merge to create a better and bigger shelter while another team help

set up another theirs. Later on, another three teams merged and a

crude mansion emerged. Then all improved the comfortability of their

living quarters by placing cushions of grass and coconut palms under

their ground sheets and leaves of banana and anahaw (English:

foot-stool palm) are propped at the exposed sides to break the entry

of drafts.

I

too set up my own shelter in the pouring rain. My T-shirt is wet as

well as my thick Blackhawk pants and 5.11 shoes. I do not mind it

and even used my Canon IXUS 145 camera to take pictures, knowing well

that water would incapacitate it. I really do not mind it at all for

I know the participants are also watching me of how I conducted

myself in a difficult situation. Inspired by my example, the CADER

volunteers began to show tenacity and perseverance and a sense of

community evolved.

Satisfied

with their grit and their resourcefulness, I reminded them that the

brain would adapt to pressure and stress in any given situation. All

you have to do is act accordingly and smartly to what you will

perceive. I proceed to the first chapter which is Introduction to

Bushcraft. In this chapter, bushcraft is described to them in the

most simple terms as possible. I even provide the nearest equivalent

to my own dialect in Cebuano about bushcraft as “panikaysikay”.

Cool.

The

participants are a mixed group of young college students and mature

family men, the oldest of which is 64 years old. Joining them is Mai

Durias, the project manager of CADER and the guys from PECOJON.

Discussions in English taken from the lecture sheets would have been

alright to a set of sophisticated assortment of individuals like

weekend hikers, mountain climbers, would-be survivalists and yuppies

but this group is different. They do not even know who Bear Grylls

is. Got my point?

The

lecture ended as it starts to get dark. Quickly, the participants

help each other in grilling the pork chops and cooking the rice. I

squeeze in between glowing charcoals a small can containing tiny

squares of denim to make charclothe. They asked what is it but I

kept my lips tight. Upon my suggestion, banana leaves are gathered

to line the tops of four long tables in the main hall right after

fraying it with fire. We will have a grand “boodle fight”

tonight. Dinner started right after a prayer. It is a silent group

but it will be a noisy lot after this night.

We

transfer to the volleyball court and a huge bonfire erupt in the

middle. Dry firewood are rare after that heavy downpour earlier.

Inspite of that, we were able to start a flame using diesel fuel.

Activity is the Campfire Yarns and Storytelling. In the Philippine

Independence Bushcraft Camp, this activity is fueled by alcoholic

drinks making it very animated and entertaining. Fr. Mark's presence

made me formal stiff and I have to wrack my brains to achieve a

string of conversations for this gathering. Good thing, I got help

from Len.

For

a good two hours, each participant tell everyone in the circle

candidly about his or her expectations of the seminar and narrate

about his or her reaction when building a simple shelter with just a

few resources at hand and no clear-cut instructions under the

onslaughts of a heavy downpour. On this occasion, natural leaders

emerged from the group. After the activity, I burrow into my

Silangan hammock in a cold rainy night.

The

second day – July 24 – is sunny. After breakfast, I begin the

next chapter of Ethical Bushcraft. There is always the danger of

overdoing things in the course of a bushcraft activity and might not

be conformable to the environment and to certain individuals or

organizations. Ethical Bushcraft guides you the proper way to use

forest resources in the best way possible, taking advantage of

knowing the plants and animals, choosing a campsite well, fire

safety, disposal of garbage the bushcraft way and be stewards of the

forest.

This

chapter is very long and is very important as well that people know

this. I know a lot of very entertaining survival TV shows that sends

the wrong messages to its audiences and I read in websites that a lot

of park managers and private land owners are beginning to complain

about destruction of plants and the aesthetics of their lands by

these weekend survivalists in the US and UK. Proper education is the

key here and this is where it starts.

As

I prepare for the next lecture, I place all my unsheathed blades on

the table before me: the AJF Gahum, the William Rodgers, the

tomahawk, the Victorinox Trailmaster, the Leatherman Juice S2, the

Mora Companion, two Seseblades sinalung and a ginunting.

Because, in a moment, the

chapter on Knife Care and Safety will start. A

knife is a tool, first and foremost, and, like any other tool, it

must be maintained sharp and free of rust. You must learn how to

sharpen and must know what are the parts of a knife as well as the

kinds of designs and edge.

It

hurts also – and, sometimes, very expensive - if you do not know

the only law (Batas Pambansa Bilang 6)

governing the use and carry of a knife here in the Philippines. It

is very important that those who participated in all my bushcraft

camps know this by heart and the procedures (and proper gestures, as

well) in declaring and surrendering your carried blades to security

checks when entering ports of entry, airports, malls and, even road

checkpoints.

Knife

safety is very important in bushcraft because, if you do not practice

that, you are bound to hurt yourself or others with you since

bushcraft is a

labor-intensive activity and directing a lot of work with a knife or

knives. As our next chapter

would be labor-intensive,

it is important that safety should be observed. Meanwhile,

people are going to fast today, including

me. There would be no noon

meal. It is part of the

learning process.

Survival

Tool-Making is next and I assigned people to

six groups. There are mature bamboo poles provided for use in this

class and soon it would be dismembered. Mature

bamboos are hard but with a sharp knife, even if it is a small one,

you can cut it as it pleases you as

long as you pay attention to

my instructions and my demo.

They

have to make for themselves individually bamboo spoons and jugs. As

a group, they would have to

make bamboo cooking pots with

conjoined segments – the

Trailhawk System

way.

The

six groups began cutting the poles even as a deluge of rain begins to

fall from the skies. I leave them be and they brought the bamboos

underneath the roof of the main hall. They

only stop when I think it is

time to continue with another

lecture about Outdoor

Cooking. On this chapter, I

discussed the different ways to preserve the edibility of vegetables,

fruits, meat and fish. They also learned the methods of cooking as

in an open fireplace, semi-closed pit and the closed way of cooking

which is done under the ground. In time, they will understand

these later in the night.

After

all had happily

showed me their crafted tools - bamboo cooking pots, spoons and

drinking jugs – I begin the

process of teaching them how to cook rice in bamboo, especially

mature bamboos. Unknown

to most, mature bamboos can

be used to cook something as much as you would use one

with green bamboos and

it is no different when you integrate it

with my Trailhawk System from

opening up the segments down to the cooking itself.

So,

while some attend to the cooking, the rest forage around for food.

Some guys have foraged along the river for snails which only a few

were found which are the neritidae and the thiaridae

species. Others opt to scrounge edible plants like horseradish,

swamp cabbage and banana trunks while a handful borrowed my two

catapults and used these to ping two free-rein chicken senseless.

Slowly

the rice from the bamboos are being transferred to frayed banana

leaves. Ah, I see another grand “boodle fight” feast in the

making. Each group occupy one table and I make the round among the

tables inspecting what viands are they going to eat? One table has

swamp cabbage adobo. Another has the core of banana trunks cooked

and set as extender for canned sardines. Then four tables shared the

native chicken estofado among them. Dinner commence at 19:45 after a

short prayer.

Since

it is raining and a campfire is not feasible, I rather have the

participants gather in the social hall of the resort for some

team-building activity initiated by the students among them and

videos of some of the things I discussed for the past two days. Two

episodes of Ray Mears are shown to the participants – the ones done

between Thailand and Vietnam (POW Survival Stories) and the other one

shot in Palawan (Desert Island Survival). Then they begin to

understand what I was talking about.

It

is another cold night, wet and omnipresent rain, as I seek the

comfort of my shelter in the darkness. My place is located at the

farthest and the highest part of the campsite where there are Mexican

lilac trees (kakawate) to fasten my hammock and canopy sheet.

The call of a night heron pierce the silence of dawn and it is just

near. Meanwhile, drops of moisture found its way into me as my sheet

begins to show signs of aging and from abuse.

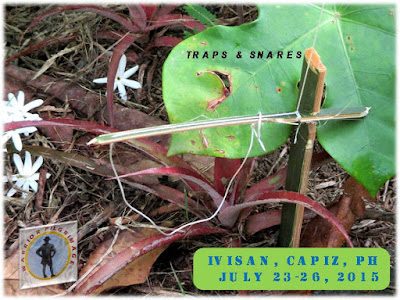

The

third day – July 25 – also shows a promise of a sunny and warm

morning. I begin to discern that rain always come knocking at or

near noon here in this part of the Visayas. While everyone are still

recovering from their sleep, I devise an Aeta-style bamboo snare that

is designed to catch a monkey or a monitor lizard and a trap that is

good for snakes, fish and lizards. Three participants caught me

doing this and made themselves two pressure-trigger snares for fowls

while another made a loop snare designed to catch small mammals.

I

took advantage of the good window of sunny weather and proceed on

with the lecture about Firecraft. As always, the importance of this

skill rely mostly on dry things and less humidity. Since it rained

the whole night and the ground is wet, I doubt if we could make fire

by friction but I could try and dry the bamboos. But first, I have

to discuss the solar magnification method which would utilize the

rays of the sun to be increased in intensity by placing a magnifying

lens between it and a tinder.

I

showed them the small blackened can which I placed on a fire on the

first night as if I am cooking it. I opened it and showed the

contents: charred cloth or charcloth. They place a magnifying lens

over it and it begins to produce smoke and ember faster than they

have known of doing it with paper. They are amazed and they begin to

ask how did I “cook” it? I showed them how with the same

air-tight can with a small hole where “fresh” denim cloth are

placed inside. It helped when I mentioned the process of making

charcoal and they can relate better the idea of the charclothe.

By

now, the sky begins to go cloudy. Solar magnification by use of a

bottled water did not have a good result so I proceed to fire-making

by friction else it rain again. There are many ways in doing that

but I start with the unfamiliar: the bow-drill method. I have pieces

of dry wood that I have brought from Cebu and I begin unravelling the

intricacies of making and performing the bow drill to the eager

participants who are now mesmerized by the simple wonders of

bushcraft.

My

several efforts only produce a smoke. I do not have the good timing

and it might be good if I let the participants try this on

themselves. Two sets of bow drills are now at work and the odor of

smoke pervade the air but no ember too. Too humid. The ground is

wet and moisture, invisible to the naked eye, easily transfers to a

porous material like dry soft wood for it acts like sponge. Worse, I

can smell the ominous coming of rain. Time to hurry this lecture and

proceed to the bamboo-saw method.

Very

popular but very effective, the bamboo saw is taught to the Boy Scout

here, which some of the participants were once had been. Similarly,

as in the bow drill, it only emitted the pungent odor of burnt wood

and the tell-tale smoke, but no ember. To prop back their sagging

confidence, I introduce them to the novel idea of lighting a fire

with a ferro rod. They could not contain their smile and their

amazement at the wonders of this inextinguishable source of fire that

worked even when wet.

My

last lecture for the day is about a kit that is very relevant to any

would-be responder: the Everyday Carry or EDC. They were a bit

confused about this term but they were able to relate again with a

smile when I asked them of the usual things that a carpenter would

bring to his work. All my EDC items get a scrutiny from sugar

sachets to a power bank to a coin purse containing loose change and a

USB memory. Some of them carried micro-EDCs but they just did not

know that. Now they are educated on the twerks of urban survival.

The

course finished before 17:00 and everybody happily heaved a sigh of

relief. I did likewise. This was a different crowd but I am able to

adjust and improvise a bit. Just some little tweaks and a good dose

of creativity. I am optimistic that I would meet this same kind of

participants and I could apply the same tricks. Anyway, all gathered

for a group picture with their certificates of training before

everyone went to their assigned tasks. Some prepared something for

dinner while four guys left the resort on board the CADER vehicle.

I

visit the room reserved and paid for my keep which I did not use for

two nights when I was with the participants. The soft bed is

inviting but it is best that I take a bath first which I have not had

the opportunity to do so for the past three days. I take a nap after

that and woke up. It is already dark but I feel refreshed. Fr. Mark

is here and I greet him a good evening. I notice a sack filled with

fresh oysters which majority of these are already in the process of

being cooked on raw embers and in boiling water.

I

sit on the long table with Fr. Mark, Len, Charlie, Joy and Mai for

dinner. I notice something familiar – a perfectly-cold bottle of

Gold Eagle Beer. It has been eons since I last drank this. That was

in the late '80s. Then I notice something new – a dish of

immaculately white elongated clams. I learned that this is called

“diwal” (English: angel-wing clam) and it is highly-valued

in Capiz as their own. Rightly so. The meat is succulently

delicious and strangely sweet. I believed I had eaten twenty pieces

during dinner plus the oysters and emptied three bottles of beer.

When

Fr. Mark left, I proceed to my room. I wake up at 07:00 on the

fourth day – July 26. My Blackhawk pants and my 5.11 shoes are

already dry. Today I would travel back to Iloilo then to Cebu but,

first, we have to be at Roxas City. I receive tokens of appreciation

from the Archdiocese of Capiz then the same vehicle that brought me

and PECOJON people here in July 23 came and whisked us back to Iloilo

with a stopover at Midway, a good restaurant located on the middle of

nowhere. Joy and I catch plane back to Cebu but Len and Charlie took

on separate destinations. Arrive home at 15:00.

The

opportunity to expand my realm of teaching bushcraft to the Province

of Capiz, especially to the volunteer emergency responders belonging

to CADER, had been made possible thru the instance of PECOJON.

PECOJON, together with partner NGOs and LGUs, are engaged in the

advocacy of developing emergency preparedness capability for the

local communities which had been hit hardest by Tropical Cyclone

Haiyan. Self-reliance skills which I have taught is just one of

their objectives to reduce the impacts of catastrophes.

Going

back to this window of opportunity, I somehow placed myself at the

edge of my wildest dreams: that of actively pursuing my passion into

something tangible, worthwhile and enjoyable. I have studied this

for a very long time considering that I have a day job which might be

affected by the conflict of how I divide my time. Sooner or later, I

will choose which would be best for me and my family's upkeep. For

now, I get to have a foretaste of the labors of this novel interest

which I am sharing to Filipinos and it is very tempting.

Document

done in LibreOffice 4.3 Writer

Posted by

PinoyApache

at

09:00

![]()

Labels: bushcraft camp, Capiz, ethical bushcraft, firecraft, Iloilo, Ivisan, knife safety, outdoor cooking, Roxas City, survivalcraft, tool making, training, travel

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment