I HAVE BEEN A

LONELY VOICE in the outdoors, propagating a strange interest here in Cebu, the

Philippines, called BUSHCRAFT. In the middle of 2009, only two people, apart

from me, could comprehend its idea and how it is done or enjoyed of as a

leisure activity. I was then in the process of distancing myself from

mainstream outdoors. I love camping with a real fire and using a knife. Uh.

Sorry. Knives.

Backpacking,

sometimes mistaken here as mountaineering, is very popular. Urbanites regularly

trekked to the mountains carrying heavy loads to spend overnight or a few days

on those barren and exposed places. They looked cool carrying branded bags with

matching shoes and brightly-colored clothes. If you look closer on their

activities, you would notice the absence of a respectable knife.

I could not

comprehend why people replaced a real knife with ceramic or plastic ones, and

sometimes by nail files? Is it because of weight? Regulations? Fear? Whatever

it was, the lack of that was influenced by no other than by ignorance. Then it

became an advocacy for me to re-introduce the knife back to camping life, the

knife-carry rights, and to educate more people about knife law, ethics, care

and safety.

When I organized

the first Philippine Independence Bushcraft Camp in 2011, the topic about the

knife was given paramount importance. It was here that the participants began

to understand the knife and it was also here that the knife culture began to

slowly reclaim its spot in Philippine outdoors, thanks to my new converts (to

include the next PIBC batches), which became the tiny sparks that started the

organization of the Camp Red Bushcraft and Survival Guild.

Recreational

bushcraft activities every weekend fascinated the outdoors community in social

media. My activities always placed the knives at stellar attraction with the

introduction of the first (and succeeding) “blade porn”, a traditional

bushcraft showcase. An online prepping community began to appear and their

members start to feature knives regularly. So were an online survivalist

community and another online group that specialized more on blades.

One of those who

participated in PIBC 2013 is a collector of expensive knives. He had been

searching in the internet for any bushcraft activity in the Philippines so he

could use his blades and it surprised him that his search brought him back to

Cebu, of all places, his home province. He is Aljew Frasco, a gentleman from

Liloan and a baker by profession. After the PIBC, he toyed on the idea of

making knives from his DIY shop.

He just wanted to

develop that skill as a hobby. That is all. Profiting from that was out of his

thoughts. He had been searching long and wide for a perfect knife – a knife

that could do all things. He found out later that he had been looking for the

wrong places and it was with him all the time and they were a combination of

threes or twos. What he lacked was time in the outdoors. The best place to test

a knife. The PIBC gave him a different perspective this time.

One day after PIBC

2013, I got a call from him. He wanted me to test a knife. He made it himself.

His first. A set of three letters were etched near the spine – AJF. His

initials. With a sheepish smile, he named the knife as the AJF Gahum. Gahum is

the literal Cebuano for “power”. Well, I thought to myself, I really need all

the power in my arm to wield this steel blade. It was heavy but it suits me

anyway and my outdoors lifestyle. I am used to hard work.

A few months

later, he asked me of my opinion of the AJF Gahum. I gave him my honest

observations; and the knife back to him. A few weeks passed and I got a call

from him again. This time, the AJF Gahum sported a new set of wooden scales

made of Philippine rosewood (Local name: narra) and Leichardt pine (hambabalod).

Heavy mechanical work on the blade surface and the tapered distal made it

lighter. It now has a convex grind and, likewise, thinner by a few micrometers.

It is now sleek, vicious and hungry. There is only one thing to do: TEST IT

OUTDOORS!

The AJF Gahum is a

straight-backed knife. A very simple one. Of a very basic design, it is 235

millimeters long from tip to hilt. The full tang that held the scales is 130 mm

from ricasso to end. It is 47 mm from

its widest measure and 6 mm at its thickest. It weighed 610 grams. With its new

scales, it looked very handsome and caused a stir of interest, desires and more

stares. It had lived up to its name. But appearances are different from

performances. It had to be worn out and break something or be broken.

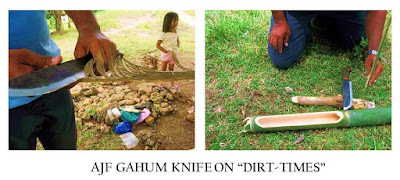

And so it became a

regular customer on my side during dirt times and it made my work on the fields

much easy, easing out my beloved tomahawk. The longer edge made cutting seamless

and it never missed wood or bamboo. The extra, yet very manageable, weight made

chopping effortless. I only have to raise it up and let gravity do its work.

The weight assures me that it is there inside its sheath all the time and it

erased my fear of it getting lost.

Weekends are my

favorite days with the AJF Gahum. I test it on hardy bamboos, whose denseness

in grain and skin could undo the superiority of branded knives into so-so ones.

The Gahum, could cut it all seamlessly whether it be on the woody part or on

wiry types whose thin tubes crack to splinters with a wrong swing. It does not

matter if it is green or matured. This big knife is native born and is made to

cut bamboo and wood, cane grass and shrubs.

The spine is

friendly to batoning sticks which guide the strong-willed Gahum to a finer

cutting tool. The same spine flaked off quartzites and iron pyrites from its

mother stones, creating sparks from the clash of 5160 carbon steel and raw, but

harder, material. As it is subjected to heavy usage, one of the rosewood scales

went missing. The other half splintered into two pieces during a knife-throwing

session. But the Leichardt wood scales remained.

For want of a

hammer, a heavy stick, or a stone, the AJF Gahum drove sharpened sticks into

the ground when I set up fly sheets for shelters. Some grounds are soft and

some need power to penetrate. It happens all the time when I carried a hammock

and where anchoring needed wooden pegs. I usually hit the top of the pegs right

on the face of the blade. The same spot over and over again and the blade had

not warped nor bent a slight angle. It is straight as ever.

I carried openly

the Gahum at my belt during the exploration phase of the Cebu Highlands Trail,

starting January 2015. The project is divided into eight segments, north to

south, and this knife had been brought and toured on the six segments. I

expected heavy knife work but I was glad it did not come to that. The

opportunity to show off the AJF Gahum in open carry was just to familiarize

locals, instead, about knife-carry rights for outdoorsmen.

The AJF Gahum,

with its bulk and appearance, travelled with me, along with six to nine of my

other knives, to Luzon, Visayas and, later, Mindanao. I did part-time classes

in bushcraft and survival when I had a day job. When I pursued full time this

journeyman occupation in 2016, I already knew how to bring my entire sharp

tools through security, legally, for just as long as you follow regulations and

protocols. Just do not carry the wrong item. Nor give a joke about bombs.

I let my students

handle the Gahum during knife dexterity sessions. After each activity, I always

examine the edge if it had dents and cracks. You would never know how people do

to other people’s knives. Especially the “uneducated” ones who see knife as

nothing but pry bars or digging tools. As a knife-carry rights advocate and

teacher, your satisfaction goes ten-fold when you see no such marks. It is not

a question of how perfect the temper of your knife is but of how your students

fully absorbed the lectures well.

If you are skilled

with a knife, you can use an AJF Gahum with a deficiency to its handle. I did

that for more than a year. The missing rosewood scales allowed me to move back

an inch to grip on the remaining scales. I used the baton stick instead to do

the work for me. I cannot tolerate an absent AJF Gahum in my activity so the

missing scales could be replaced. Despite the insistence of the maker to do

that task for free.

However, I did acquiesce

to the wishes of the maker at last. He asked me what material would I want to

replace the scales. I provided him industrial micarta, a hardy material which

were shaped to hold superheated shaft bearings of mining machinery that I found

in an abandoned mine in Misamis Oriental in 2012. The mere fact that it is for

industrial use and bear the Hitachi logo, makes it indestructible and would

stay for keeps.

Just in time

before the start of the PIBC 2017, I held the AJF Gahum once again. This time,

it sported a different look and character: dark, brooding, unpredictable and

incorruptible. From a blade with flamboyant two-toned scales, it now sports

gloomy black scales. More like the Dark Knight. I like it that way. Very

proletarian. Knives are just tools and should be used according to what it was

intended for when early man invented it.

The AJF Gahum,

however, is not a perfect knife. It has to be paired with a smaller one so I

could accomplish my tasks outdoors. The built, temper and design are perfect in

tropical settings. The edge has dulled just a bit and I liked it that way for

my classes. I could not remember the time I sharpened it myself. It never came

to that. I am a satisfied recipient of an excellent knife and it is a privilege

to own the first of just a few blades made by AJF.

Document done in LibreOffice 5.3

Writer

No comments:

Post a Comment